Introduction

The structural design of buildings and bridges requires meticulous evaluation of materials to ensure safety, longevity, and efficiency. One material property that is important to understand when designing such structures is the modulus of elasticity so that serviceability deflections can be analyzed. Steel and wood have long been cornerstones of structural design and have thorough design standards on how to interpret and apply the properties of the material. Although the design standards that govern wood and steel design differ in the approach as to how they define the material properties, both agree on the use of the mean modulus for the serviceability deflection analysis. Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) has been used successfully for buildings and bridges over the past several decades, however, the design standards of FRP have not caught up to the growth in use of this material. It is the purpose of this article to defend the use of the mean modulus for evaluating serviceability deflections because many applications with FRP are limited by deflection before the strength limits are reached. The use of mean modulus values aligns with the approach taken by AASHTO, NDS and ASCE for steel and wood design.

Design Modulus: Steel and Wood

Steel design (AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Specification and AISC Steel Construction Manual) uses a mean modulus of 29 MSI for the serviceability deflection checks. This approach acknowledges the inherent variability in the actual modulus of steel, which can deviate as much as +/-5% from the mean value.

Wood design (National Design Specification for Wood Construction) uses a mean species modulus with moisture and temperature reductions for the serviceability deflection analysis. This approach acknowledges that the mean modulus is greater than the minimum modulus which represents the lower bound of what is possible in the species and is primarily used in life safety checks associated with buckling.

Both steel and wood design acknowledge that serviceability deflection analysis is not a life safety analysis and thus use the mean modulus is utilized for these serviceability analysis checks. Wood, unlike steel, is susceptible to a reduction in the modulus due to high service temperatures and moisture content so those reductions are included with the mean modulus for serviceability deflection analysis.

Design Modulus: Fiber Reinforced Polymer

Without cohesive standards for FRP design, there have been multiple design approaches followed for the control of deflection in FRP structures. The process outlined in this article aims to give guidance to a logical design approach that conforms FRP design methods to that of steel and wood.

Mean Modulus

The use of the mean tested modulus for FRP is recommended in the design of buildings and bridges. This value can either be the flexural modulus determined from testing the structural member in question (For example an I-beam, c-channel or angle) or the lower value of the FRP’s tension or compression moduli as determined from coupon testing.

Service Temperature Reduction

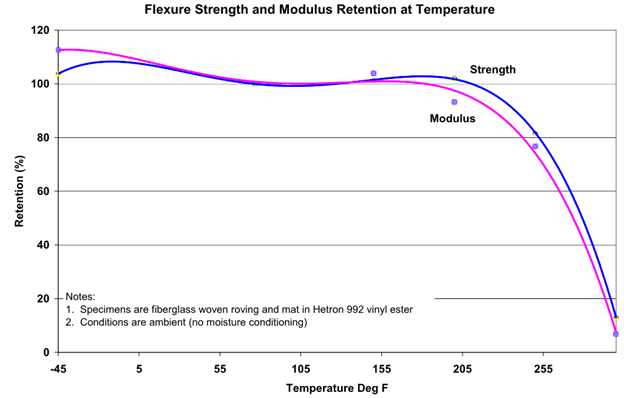

FRP structures, like wood, can be susceptible to a reduction in modulus at elevated service temperatures, therefore there are instances when a service temperature reduction factor is appropriate. Numerous studies have been done on the modulus reduction of FRP composites that show a high correlation to the glass transition temperature of the resin. Figure 1 depicts a graph of the property retention of a FRP sample at increasing temperatures with a high drop off in retention upon approach and surpassing of the glass transition temperature. When the service temperature gets within 50-100°F of that glass transition temperature a reduction factor should be considered. Most infrastructure applications use either polyester or vinyl ester resin systems in the FRP composites that have glass transition temperatures in the range of 160°F to 230°F with vinyl ester resin the glass transition temperature is typically slightly higher than the glass transition temperature of polyester resins. For all resins, the glass transition temperature should be at least 50°F above the service temperature. For applications that have their service temperature between 50°F and 99°F above the glass transition temperature a reduction factor of 0.9 should be used to account for the reduction in modulus.

Figure: Correlation shown between glass transition temperature of vinyl ester resin and modulus retention in FRP specimen.

Other Considerations

Notably not included in the modulus reduction factor is long term environmental or moisture absorption reductions. Although FRP materials do absorb small amounts of moisture over time, even at full saturation of moisture at the service temperatures experienced in civil infrastructure there is very little degradation of the modulus.

Following the steel and wood design approach, the long-term degradation of the modulus is not considered part of the serviceability deflection analysis. For example, steel does use expected corrosion loss estimates over time in the service deflection checks nor does wood account for its degradation over time in the serviceability deflection analysis.

The use of mean modulus is not always appropriate for design, strength checks that require the use of modulus, primarily in buckling analysis, should use the lower bound value of the modulus. This is the same approach that the National Design Specification for Wood Construction outlines with its E and Emin values. For FRP this would involve using the ASTM D7290 statistically reduced modulus in combination with the temperature reduction factor discussed above and a long-term environmental reduction factor (typically 0.9 for exterior applications).

Conclusion

The use of mean modulus and temperature-dependent reduction factors represents a significant step forward in the design process and implementation of Fiber Reinforced Polymer in structural engineering. This approach aligns FRP serviceability deflection analysis with established practices for steel and wood. As the demand for sustainable and innovative materials continues to grow, the careful consideration of FRP’s unique properties, coupled with an industry consistent design approach, ensures that the potential of this material is more fully realized in the construction of safe, efficient, and enduring buildings and bridges.